As a small child growing up with my paternal grandparents in north central China’s deep pine forest mountains, I was forever curious about my grandmother’s tiny crooked feet. Every time she sat on the small, wooden stool facing the sod wall in the corner of our one-room house to soak her feet in the big iron washbasin full of steamy water, I’d rush over to get an eyeful.

As a small child growing up with my paternal grandparents in north central China’s deep pine forest mountains, I was forever curious about my grandmother’s tiny crooked feet. Every time she sat on the small, wooden stool facing the sod wall in the corner of our one-room house to soak her feet in the big iron washbasin full of steamy water, I’d rush over to get an eyeful.

My grandmother’s three-inch-long bound feet looked like a pair of pale, naked dead birds made out of wheat flour dough. Each big toe stood alone pointing forward while her four small toes were crush-bent underneath her sole. The back of her feet arched up like a smooth, round steamed bun with each sole a hollow cleft after the front feet and heel were crunch-pushed toward each other.

“Get out of here, you nosy creature!” Grandmother would yell, panicked by my prying eyes, hurriedly stretching out her big, knobby field hands over her feet. “What’s there to look at? Nothing but these two ugly things! Ouch, so hurting …” her eyes squeezed shut, her toothless mouth gasping, every wrinkle in her sun-browned face and her high-cheek-bones, carved in pain.

“Damn my parents!” Grandmother would say between her gasps. “Yes, I dare to speak unfavorable words against my revered father and mother, even though they have passed. Look how they hurt me …”

Born in 1912, Grandmother was one of the last crop of victims of the barbaric Chinese foot-binding. For one thousand years, all little girls between ages three and five, rich or poor, had to have their tender little feet maimed into a pair of exquisite three-inch-long flowers shaped like “golden lilies.” Chinese men were said to relish as erotic their women’s tiny pointed feet, the original flesh-and-blood version of today’s Western stilettos.

Grandmother was five years old when, one day, her mother soaked her feet in special fragrant herbal water. As Grandmother screamed in flooding tears of pain, her mother crushed, bent and force-wrapped her feet into two iron-tight pointed stubs with 裹腳布 guo-jiao-bu, a ten-foot-long strip of black cotton cloth, as her own mother did to hers when she was a child. The cloth was not to be loosened for months at a time, and then, only to let the rotting pus out before they were wrapped back up, tighter.

“It’s for your own good, my daughter,” her mother sobbed. “So, a good man will want to marry you.”

All the while, her father reminded her to behave like a demure lady.

Grandmother’s feet felt like on fire, slowly roasting. The excruciating pain kept her awake all night. She dared not cry out loud but whimper and sob quietly for fear of her father scolding her.

“They didn’t have to harm me like this.” Tears ran down Grandmother’s cheeks, as she rubbed her arched-up-like-a-cat’s-back deformed feet.

The flesh-rotting, bone-crushing custom was abolished in 1911, one year before Grandmother was born, when the Republic of China overthrew the Manchu Dynasty. The new government would send out special inspectors to the remote mountain villages to catch and punish people who still bound their young daughter’s feet.

“Other girls my age in my village were spared by their parents, but no, not that knuckle-headed stubborn father of mine. He insisted on sticking to the despicable old tradition. Every time the inspectors came to the village to catch the illegal foot-binding, he’d carry me up to the attic, hide me under stacks of hay, hush me into silence and warn me not to make a sound. Damn that fool!

“Why didn’t they find me a rich husband instead of this useless weakling peasant grandfather of yours?” Grandmother lifted the front of her faded black cotton shirt to wipe her tears. “O, how I suffered working alongside him like a beast in the cornfields.”

Grandmother gave birth to eight babies, my father her first-born, during the fourteen-year span (1931-45) of the brutal Japanese invasion of China during WWII. On her painful stubby feet, Grandmother would lead her small children in hushed silence at midnight running for their lives into the deep mountain caves.

Throughout her eighty-six years of life, Grandmother cried tears of pain over her “golden lily” feet.

As her first grandchild born a girl instead of a gold-valued boy, I was a disappointment to Grandmother. My earliest memory is of her eyeing me hard, sideways: “Those tiny slit eyes and that pig snout mouth look just like that bad-omen ugly mother of yours.”

But there was one thing Grandmother made me feel good about myself.

My feet.

“Oh, just look at these darling feet.” Grandmother would reach out to caress my child’s feet, a look of great envy and rare affection in her now-soft eyes. “They are gorgeous … so flat … so free to grow. Lucky child, born in good times. Your feet don’t have to suffer. Oh, they are meaty, big, plump feet just like mine. You would have suffered terrible pain just like I did. Girls with skinny, smaller feet didn’t suffer as badly.”

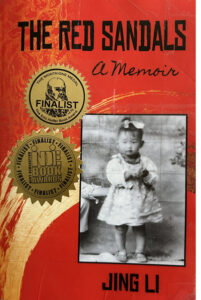

On the morning of June 1, 1962, International Children’s Day, I woke up smiling and giggling, my six-year-old heart leaping for joy. Today was going to be a very special day because Grandmother’s promise was to make my dream come true. I was finally allowed to wear the beautiful red sandals my parents sent from the city.

I’d been waiting for this moment like a restless ant on a hot stove. Grandmother had kept my red sandals locked, alongside my beautiful doll, in her scrap bundle inside the big black floor chest. Every time I saw her reach down into the chest for her treasured bundle, I’d hurry over for a glimpse of my red sandals. The bright color was just like the bright red wild berries Grandpa picked for me on his way down the mountains after toiling all day in the commune’s cornfields. Like the comforting glow of the fire in our brick stove on a cold winter’s day, it warmed my heart.

But Grandmother wouldn’t allow me to try the shoes on. She said they were too pretty, too brand-new for my dirty feet. She kept saying that my feet were not big enough. I’d have to wait till the next June 1.

Today was finally the day! My face couldn’t stop smiling. I couldn’t wait to put the red sandals on and show off to my first-grade classmates. This was the first time I felt good that my parents lived in the faraway-city with my two younger brothers.

I clapped, cheered, and jumped for joy as Grandmother set the sandals in front of me. Sitting down on the wooden floor stool, I kicked off my homemade cloth shoes and carefully placed my feet on top of my old shoes to avoid touching the dusty earthen floor. Gingerly, I began to inch my feet into the cool, smooth and soft-like-rubber but magically see-through red sandals.

Oh, no! Why were my heels still hanging out but the shoes were already full? Well, no matter. I should just push hard. Grandmother had said the shoes were ready for my feet today. They had to fit. But as I finally stuffed my heels inside, my big toes were crunched up tight and stiff, butting heads like the thick long stick Grandpa used to prop against our door at night. My feet were hurting badly.

I couldn’t understand it — Grandmother had said this year was the right time when the red sandals would fit. Why did my feet feel too big for them? Today, my first-grade class was going to parade through the village to celebrate Children’s Day. I had to wear them. I stood up but could only walk unsteadily, like Grandmother on her painful, tiny, stubby, three-inch bound feet.

I limped around the floor, hoping and wishing for my red sandals to become bigger. But they didn’t. I sucked in the pain and hobbled out to join my classmates. But the pain became worse, and finally unbearable. Halfway through the parade, I took off my red sandals and held them in my hands, walking barefoot on the village’s rocky dirt street.

Once home, I quietly handed over my dream red sandals to Grandmother.

“Why?” asked Grandmother simply. “Don’t you want to wear them?”

In tears, I shook my head, not knowing what to say, startled that she didn’t look surprised.

Sitting down on the stool, I inspected my feet. Blood seeped out quietly from under my big toenails. The right toenail was broken in half vertically with a bulging ridge.

I never saw my beautiful red sandals again.